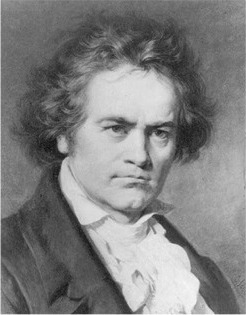

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptized December

17, 1770 d. March 26, 1827) was a German composer, the predominant

musical figure in the transitional period between the Classical and

Romantic eras. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers

of all time.

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptized December

17, 1770 d. March 26, 1827) was a German composer, the predominant

musical figure in the transitional period between the Classical and

Romantic eras. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers

of all time.

Contents

Early Life

Beethoven was born in Bonn in the archbishopric of Cologne in

western Germany. His parents were Johann van Beethoven (1740-92)

and Magdalena Keverich van Beethoven (1744-87). Ludwig's father

was himself a musician employed in the Electoral court at Bonn.

The family was Flemish in origin (hence "van", not "von")

and can be traced back to Mechelen, now in Belgium. They named

their son after his grandfather. Beethoven's parents had a total

of seven children, of whom only three survived infancy. These were

Beethoven and his two younger brothers, Caspar Anton Carl, born

1774, and Nikolaus Johann, born 1776.

Beethoven began his musical education under the tutorship of his

father, who was an alcoholic and is believed to have beaten him

in the course of his lessons. The child's musical talent manifested

itself early, and his father attempted unsuccessfully to exploit

the boy as a child prodigy.

In 1779 Beethoven became the protegé of Christian Gottlob

Neefe, who taught him composition. Beethoven soon began working

with Neefe as assistant organist, first on an unpaid basis (1791),

and then as paid employee of the court (1784). His first three

piano sonatas, the so-called "Kurfürst" sonatas,

were published in 1783. During this time, Beethoven's talent was

noticed and appreciated by the reigning prince, Elector Maximilian

Franz (1756-1801), who subsidized his musical studies.

In 1787, Beethoven traveled to Vienna hoping to study with Mozart.

Scholars disagree on the authenticity of a story whereby Beethoven

is said to have played for Mozart and impressed him. After just

two weeks in Vienna, Beethoven learned that his mother was severely

ill, and he was forced to return home. His mother died shortly

thereafter, and the father lapsed into incapacitating alcoholism.

Beethoven thus became responsible for the care of his two younger

brothers, and he spent the next five years in Bonn.

In 1789, he succeeded in obtaining a legal order by which half

of his father's salary was paid directly to him for support of

the family. Another source of income was payment for Beethoven's

service as a violist in the court orchestra. This familiarized

Beethoven with three of Mozart's operas performed at court in this

period.

Establishing his career in Vienna

With the Elector's help, Beethoven moved again to Vienna in 1792.

Beethoven did not immediately set out to establish himself as a

composer, but rather devoted himself to study and to piano performance.

Working under the direction of Joseph Haydn, he sought to master

counterpoint, and he also took violin lessons. At the same time,

he established a reputation as a piano virtuoso and improviser

in the salons of the nobility, often playing the preludes and fugues

of J. S. Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier.

With Haydn's departure for England in 1794, Beethoven was expected

by the Elector to return home. He chose instead to remain in Vienna,

continuing the instruction in counterpoint with Johann Georg Albrechtsberger

and other teachers. Although his stipend from the Elector expired,

a number of Viennese noblemen had already recognized his talent

and offered him financial support, among them Prince Joseph Franz

Lobkowicz, Prince Karl Lichnowsky, and Baron Gottfried van Swieten.

Beethoven's first public performance in Vienna was in 1795, with

his Second (or perhaps First) Piano Concerto; and in the same year

were published the first of his compositions to which he assigned

an opus number, the piano trios of Opus 1. By 1800, with the premiere

of his First Symphony, Beethoven was considered one of the most

important of a generation of young composers who followed after

Haydn and Mozart.

During his early career as a composer, Beethoven concentrated

first on works for piano solo, then string quartets, symphonies,

and other genres. This was a pattern he was to repeat in the "late" period

of his career (see below). Thus, 12 of Beethoven's famous series

of 32 piano sonatas date from before 1802, and could be considered

early-period works; of these, the most celebrated today is probably

the "Pathétique", Op. 13. The first six quartets

were published as a set (Op. 18) in 1800, and the First and Second

Symphonies premiered in 1800 and 1802.

All musical authorities agree that Beethoven's early work was

closely modeled on that of Haydn and Mozart. However, Beethoven's

own musical personality is still very much evident even at this

stage. This is seen, for instance, in his frequent use of the musical

dynamic sforzando, found even in the "Elector" sonatas

for piano that Beethoven wrote as a child. Some of the longer piano

sonatas of the 1790's are written in a rather discursive style

quite unlike their models, making use of the so-called "three-key

exposition".

Loss of hearing

Around 1801, Beethoven began to lose his hearing. He suffered

a severe form of tinnitus, a "roar" in his ears that

made it hard for him to appreciate music and he would avoid conversation.

The cause of Beethoven's deafness is unknown, but it has variously

been attributed to syphilis, lead poisoning, typhus, or possibly

even his habit of immersing his head in cold water to stay awake.

Over time, his hearing loss became acute: there is a well-attested

story that, at the premiere of his Ninth Symphony, he had to be

turned round to see the tumultuous applause of the audience, hearing

nothing. In 1802, he became depressed, and considered committing

suicide. He left Vienna for a time for small Austrian town of Heiligenstadt,

where he wrote the "Heiligenstadt Testament", in which

he resolved to continue living through his art. He continued composing

even as his hearing deteriorated. After a failed attempt in 1811

to perform his own "Emperor" Concerto, he never performed

in public again.

As a result of Beethoven's hearing loss, a unique historical record

has been preserved: he kept conversation books discussing music

and other issues, and giving an insight into his thought. Even

today, the conversation books form the basis for investigation

into how he felt his music should be performed, and his relationship

to art - which he took very seriously.

There are a variety of theories as to why Beethoven suffered from

hearing loss, from illness to lead poisoning. The oldest explanation,

from the autopsy of the time, is that he had a distended inner

ear which developed lesions over time. This theory is outlined

in Beethoven et les malentendus by Maurice Porot et Jacques Miermont.

Russell Martin argued, from analysis done by Walsh and McCrone

on a sample of Beethoven's hair, that there were alarmingly high

levels of lead in Beethoven's system. And that high concentrations

of lead can lead to bizarre & erratic behaviour, including

rages. Another symptom of lead poisoning is deafness. In Beethoven's

era, lead was used widely without true understanding of the damage

it could lead to: in sweetening wine, finishes on porcelain, and

even medicine. The investigation of this link was detailed in the

book, "Beethoven's Hair : An Extraordinary Historical Odyssey

and a Scientific Mystery Solved". While the likelihood of

lead poisoning is very high, the deafness associated with it seldom

takes the form that Beethoven exhibited. It is more likely that

his generally bad health as he grew older was related to plumbism

rather than his hearing loss.

The Middle Period

Around 1802 he declared "I am but lately little satisfied

with my works, I shall take a new way." The first major work

of this new way was the "Eroica" Symphony in E flat.

While other composers had written symphonies with implied programs,

or stories, this symphony was also longer and larger in scope than

any other written. It made huge demands on the players, because

at that time there were few orchestras devoted to concert music

that were independent of royal or aristocratic patrons, and hence

performance standards at concerts were often haphazard. Nevertheless,

it was a success.

The Eroica was one of the first works of Beethoven's so-called "middle

period", or "Heroic Period", a time when Beethoven

composed highly ambitious works, often heroic in tone, that extended

the scope of the classical musical language Beethoven had inherited

from Haydn and Mozart. The middle period work includes Symphonies

3-8, the string quartets 7-11, the Waldstein and Appassionata piano

sonatas, the opera Fidelio, the Violin Concerto and many other

compositions. During this time Beethoven earned his living partly

from the sale and performance of his work, and partly from subsidies

granted by various wealthy nobles who recognized his talent.

The work of the middle period established Beethoven's reputation

as a great and daring composer. In a review from 1810, he was enshrined

by E. T. A. Hoffman as one of the three great "Romantic" composers;

Hoffman called Beethoven's Fifth Symphony "one of the most

important works of the age".

The middle period ended with a flourish around 1814, with the

Seventh and Eighth Symphonies and the third--and at last, successful--version

of Fidelio. It was around this time that Beethoven's popularity

with the contemporary public reached its apogee, and he was almost

universally regarded as the greatest of living composers.

Late Beethoven

However, there soon followed a deep crisis in Beethoven's personal

life, possibly in his artistic life as well. His output dropped,

and one critic even wrote that "the composing of great works

seems behind him". The few works that date from this period

are often of an experimental character. They include the song cycle "An

die ferne Geliebte" and the piano sonata Opus 90, works which

inspired later generations of Romantic composers. This period also

produced the extraordinarily expressive, almost incoherent, song "An

die Hoffnung" (Opus 94).

Then Beethoven began a renewed study of older music, including

works by J. S. Bach and Handel, then being published in the first

attempts at complete editions. He composed "The Consecration

of the House" overture, which was the first work to attempt

to incorporate his new influences. But it is when he returned to

the keyboard to compose his first new piano sonatas in almost a

decade, that a new style, now called his "late period",

emerged.

The works of the late period are commonly held to include the

last five piano sonatas and the Diabelli Variations, the last two

sonatas for cello and piano, the late quartets (see below), and

two works for very large forces: the Missa Solemnis and the Ninth

Symphony ("Choral"), perhaps Beethoven's best known work.

The Ninth Symphony is the first to use a chorus, and its dimensions

were, again, larger than any previous work.

Beethoven then turned to writing string quartets - the war between

Austria and France had devastated his finances - for 100 gold ducats

each. This series of quartets - the "late quartets" -

would go far beyond what either musicians or audiences were ready

for at that time. One musician commented that "we know there

is something there, but we do not know what it is." Composer

Louis Spohr called them "indecipherable, uncorrected horrors," though

that opinion has changed considerably from the time of their first

bewildered reception. They would continue to inspire musicians

- from Richard Wagner to Béla Bartók - for their

unique forms and ideas.

The late quartets are now widely considered to be Beethoven's

greatest works. They are a manifestation of his lifelong spiritual

progress, and deviate radically from almost everything he had ever

written up until that point. And of the late quartets, Beethoven's

favourite was the quartet op.131 in C# minor, upon hearing which

Schubert is said to have remarked, "After this, what is left

for us to write?"

Beethoven's health had been bad for most of his life, worsening

even as he composed these last works; in his last months he became

seriously ill. He died on March 26th, 1827, after several operations

to relieve abdominal swelling, and a subsequent infection. Unlike

in the case of Mozart, who was buried in a pauper's grave, 20,000

Viennese citizens lined the streets at Beethoven's funeral.

Musical style and innovations

Beethoven is viewed as a transitional figure between the Classical

and Romantic eras of musical history. He built formally on the

principles of sonata form and motivic development that he had inherited

from Haydn and Mozart, but expanded their scope, writing longer

and more ambitious movements. The work of Beethoven's middle period

is celebrated for its frequently heroic form of expression, and

the works of his late period for their intellectual depth.

Personal beliefs and their musical influence

Beethoven was much taken by the ideals of the Enlightenment. He

initially dedicated his third symphony, the Eroica, to Napoleon

in the belief that the general would sustain the democratic and

republican ideals of the French Revolution, but in 1804 crossed

out the dedication as Napoleon's imperial ambitions became clear,

replacing it with "to the memory of a great man". The

fourth movement of his Ninth Symphony is a setting of Schiller's

ode An die Freude ("To Joy"), an optimistic hymn championing

the brotherhood of humanity.

Scholars disagree on Beethoven's religious beliefs and the role

they played in his work. For discussion, see Beethoven's religious

beliefs.

Beethoven as fictional character

Beethoven's larger-than-life persona has led many authors and

filmmakers to incorporate him into works of fictionalized biography,

among them Beethoven Lives Upstairs by Barbara Nichol and Scott

Cameron and the popular 1994 film Immortal Beloved.

Beethoven was the title character in the Trans-Siberian Orchestra's

concept album, Beethoven's Last Night. In it, he makes a deal with

the Devil to ease the suffering of a child sitting outside his

door.