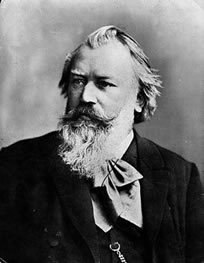

Johannes Brahms (May 7, 1833 – April 3, 1897) was a German composer of classical music. Brahms was considered by many to be the "successor" to

Beethoven, and his first symphony was described by Hans von Bülow as "Beethoven's tenth symphony" (the nickname is still used).

Life

Brahms was born in Hamburg. His father, who gave him his first music lessons, was a double bassist. Brahms showed early promise on the piano and helped to supplement the rather meager family income by playing the piano in restaurants and theaters, as well as by teaching. It is a widely-told tale that Brahms had to play the piano in bars and brothels as a child, but this is now doubted by scholars. For a time, he also learned the violoncello, although his progress was cut short when his teacher absconded with Brahms's instrument.

The young Brahms gave a few public concerts, but did not become well known as a pianist (although in later life he gave the premieres of both his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1859 and his Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1881).

The young Brahms gave a few public concerts, but did not become well known as a pianist (although in later life he gave the premieres of both his Piano Concerto No. 1 in 1859 and his Piano Concerto No. 2 in 1881).

He also began to compose, but his efforts did not receive much attention until he went on a concert tour with Eduard Reményi in 1853. On this tour he met Joseph Joachim, Franz Liszt, and later was introduced to the great German composer Robert Schumann. Reményi was, however, offended by Brahms' failure to praise Liszt's 'Sonata in B minor' wholeheartedly on a visit to the Court of Weimar where Liszt was the court musician. Many of Brahms' friends cited that Reményi, being the polished courtier, had expected the younger Brahms to conform to common practice of politely applauding a celebrity's piece which Brahms either failed to do or did not appear to do so with condescending compliment. He told Brahms that their friendship must end although it was not clear as to whether Liszt felt offended or otherwise. Joachim, however was to become one of his closest friends, and Schumann, through articles championing the young Brahms, played an important role in alerting the public to the young man's compositions. Brahms also became acquainted with Schumann's wife, the composer and pianist Clara, 14 years his senior, with whom he carried on a lifelong, emotionally passionate, but always platonic relationship. Brahms never married.

In 1862 he settled permanently in Vienna and began to concentrate fully on composing. With work such as the German Requiem, Brahms eventually established a strong reputation and came to be regarded in his own lifetime as one of the great composers. This may have given him the confidence finally to complete his first symphony; this appeared in 1876, after about ten years of work. The other three symphonies then followed in fairly rapid succession (1877, 1883, 1885).

Brahms frequently traveled, both for business (concert tours) and pleasure. He often visited Italy in the springtime, and usually sought out a pleasant rural location in which to compose during the summer.

In 1890, the 57-year-old Brahms resolved to give up composing. However, as it turned out, he was unable to abide by his decision, and in the years before his death he produced a number of acknowledged masterpieces, including the two clarinet sonatas Op. 120 (1894) and the Four Serious Songs (Vier ernste Gesänge) Op. 121 (1896).

While completing the Op. 121 songs Brahms fell ill of cancer (sources differ on whether this was of the liver or pancreas). His condition gradually worsened and he died on April 3, 1897. Brahms is buried in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna.

Works

Brahms wrote a number of major works for orchestra, including four symphonies, two piano concertos, a Violin Concerto, a Double Concerto for violin and cello, and the large choral work A German Requiem (Ein deutsches Requiem). Brahms was also a prolific composer in the theme and variation form, having notably composed the Variations and Fugue on a theme by Händel, Paganini Variations, and Variations on a Theme by Joseph Haydn, along with other lesser known sets of variations.

Brahms also wrote a great deal of work for small forces. His many works of chamber music form part of the core of this repertoire, as does his solo piano music. Brahms is also considered to be among the greatest of composers of lieder, of which he wrote about 200.

Brahms never wrote an opera, nor did he ever write in the characteristic 19th century form of the tone poem.

Influences on Brahms

Brahms venerated Beethoven, perhaps even more than the other Romantic composers did. In the composer's home, a marble bust of Beethoven looked down on the spot where he composed. Brahms's works contain what some of his contemporaries considered to be outright imitations of Beethoven's work, including the Ninth Symphony (regarding the similar - only in form - themes found in the last movements of Brahms's 1st and Beethoven's 9th symphonies) and the Hammerklavier sonata.

Brahms also loved the earlier Classical composers Mozart and Haydn. He collected first editions and autographs of their works, and also edited performing editions.

Brahms's affection for the Classical period may also be reflected in his choice of genres: he favored the Classical forms of the sonata, symphony, and concerto, and frequently composed movements in sonata form. In general, Brahms can be regarded as the most Classical of all the Romantic composers. This set him in contrast to the acolytes of the more progressive Richard Wagner, and the divide between the two schools was one of the most notable features of German musical life in the late 19th century.

A quite different influence on Brahms was folk music. Brahms wrote settings for piano and voice of 144 German folk songs, and many of his lieder reflect folk themes or depict scenes of rural life. His Hungarian dances were among his most profitable compositions, and in orchestrated versions remain well known today.

Brahms was almost certainly influenced by the technological development of the piano, which reached essentially its modern form during his lifetime. Much of Brahms's piano music and many of his lieder make use of the deep bass notes and the pedal to obtain a rich and powerful sound.

Brahms's personality

Like Beethoven, Brahms was fond of nature and often went walking in the woods around Vienna. He often brought penny candy with him to hand out to children. To adults Brahms was often brusque and sarcastic, and he sometimes alienated other people. He also had predictable habits which was noted by the Viennese press such as his daily visit to his favourite 'Red Hedgehog' tavern in Vienna and the press also particularly took into account his style of walking with his hands firmly behind his back complete with a caricature of him in this pose walking alongside a red hedgehog. Those who remained his friends were very loyal to him, however and he reciprocated in return with equal loyalty and generosity. He was a lifelong friend with Johann Strauss II though they were very different as composers. Brahms even struggled to get to the Theater an der Wien in Vienna for Strauss' premiere of the operetta Die Göttin der Vernunft in 1897 before his death. Perhaps the greatest tribute that Brahms could pay to Strauss was his remark that he would have given anything to have written The Blue Danube waltz. An anecdote dating around the time Brahms became acquainted with Strauss is that the former cheekily inscribed the words 'alas, not by Brahms!' on the autograph score of the famous 'Blue Danube' waltz.

Starting in the 1860's, when his works sold widely, Brahms was financially quite successful. He preferred a modest life style, however, living in a simple three-room apartment with a housekeeper. He gave away much of his money to relatives, and also anonymously helped support a number of young musicians.

Brahms was an extreme perfectionist. For instance, it is thought that the symphony we know as the First may not have been the first he composed, since Brahms very often destroyed completed works that failed to meet his standard of quality. Another factor that contributed to Brahms's perfectionism was that Schumann had announced early on that Brahms was to become the next great composer like Beethoven, a prediction that Brahms was determined to live up to. This prediction hardly added to the composer's self-confidence, and may also have contributed to the delay in producing the First Symphony. However, Clara Schumann noted before that Brahms' First Symphony was a product that was not reflective of Brahms' real nature as she felt that the final exuberant movement was 'too brilliant' as she was encouraged by the dark and tempestuous opening movement when Brahms first sent to her the initial draft. However, she recanted in accepting his sunny Second Symphony and was a lifelong supporter of that famous work in D major, one of Brahms' rare key usage.

Books about Brahms

- Johannes Brahms: Life and Letters, by Brahms himself, edited by Styra Avins, translated by Josef Eisinger (1998). A biography by way of comprehensive footnotes to a comprehensive collection of Brahms's letters (some translated into English for the first time).

- Brahms, His Life and Work, by Karl Geiringer, photographs by Irene Geiringer (1987, ISBN 0306802236). A bio and discussion of his musical output, supplemented by and cross-referenced with the body of correspondence sent to Brahms.